STOP THE DEMONIZATION: Changing how we talk to “our side” about the "other side"

I often feel a kind of emotional whiplash as I move back and forth between California, where I live now, and Oklahoma and Kansas, where I grew up and still have dear family and friends.

In San Francisco, I hear Blues complain about Reds — how dangerous, ignorant, or cruel they seem. In Oklahoma, I hear Reds complain about Blues — how dangerous, clueless, or cruel they seem.

Each side thinks the other is idiotic. "They" are the problem.

This pains me. I love people on both “sides.” I know them to be intelligent, generous, and kind. And yet, when conversations shift to politics, they slip into familiar roles: either the “victim” (complaining about how awful the other side is), or the “villain” (eviscerating the other side with no holds barred).

The Deeper Problem: The Gossip Mill

After months of thinking about how to help people talk to their Beloveds on the "other side" of the political aisle, I’ve realized that though such dialogue is important, it is not enough.

The deeper problem—and opportunity—lies in how we talk to our own side about the "other side."

I call it the Toxic Polarization Gossip Mill: those “delicious“ conversations where we complain about the “other side,” reinforce one another's negative assumptions, and walk away feeling more certain–and more superior–than before.

While I call it "gossip," it’s actually something far more destructive: demonization. It’s the act of making our fellow human beings less than human.

These toxic conversations don’t just reflect polarization. They create it.

A Lesson from the Workplace

I first learned about the toxic gossip mill in my twenties, when my employer hired a wise consultant, Diana McClain Smith 1. She challenged us to rethink what it means to be a good friend or a colleague.

Before she worked with us, when someone complained to us about another person, our habit was to “pile on”: to offer confirming stories and additional evidence that the other person was indeed wrong, clueless, or problematic.

Diana taught us a different, braver path:

Listen. Let the person vent briefly.

Gently challenge. Offer information that contradicts their assumptions.

Point out what they might be missing. Help them see where they are jumping to conclusions.

Encourage direct conversation. Invite them to speak directly with the person to understand their point of view and resolve issues–not just complain about them.

This practice fundamentally changed how we related to one another.

Since then, I’ve supported many clients in making this same shift — transforming their toxic gossip mill into a culture of direct, respectful problem-solving. People stop complaining behind people’s backs and start speaking directly to them. They replace assumptions with questions. They initiate uncomfortable conversations instead of avoiding them.

Over time, trust grows. Misunderstandings surface earlier and are resolved more quickly. Relationships get better, instead of quietly eroding.

I believe this practice can also make our country more resilient. The same muscles that heal a team—listening, challenging with compassion, and encouraging direct human contact—are the muscles we need to heal our democracy.

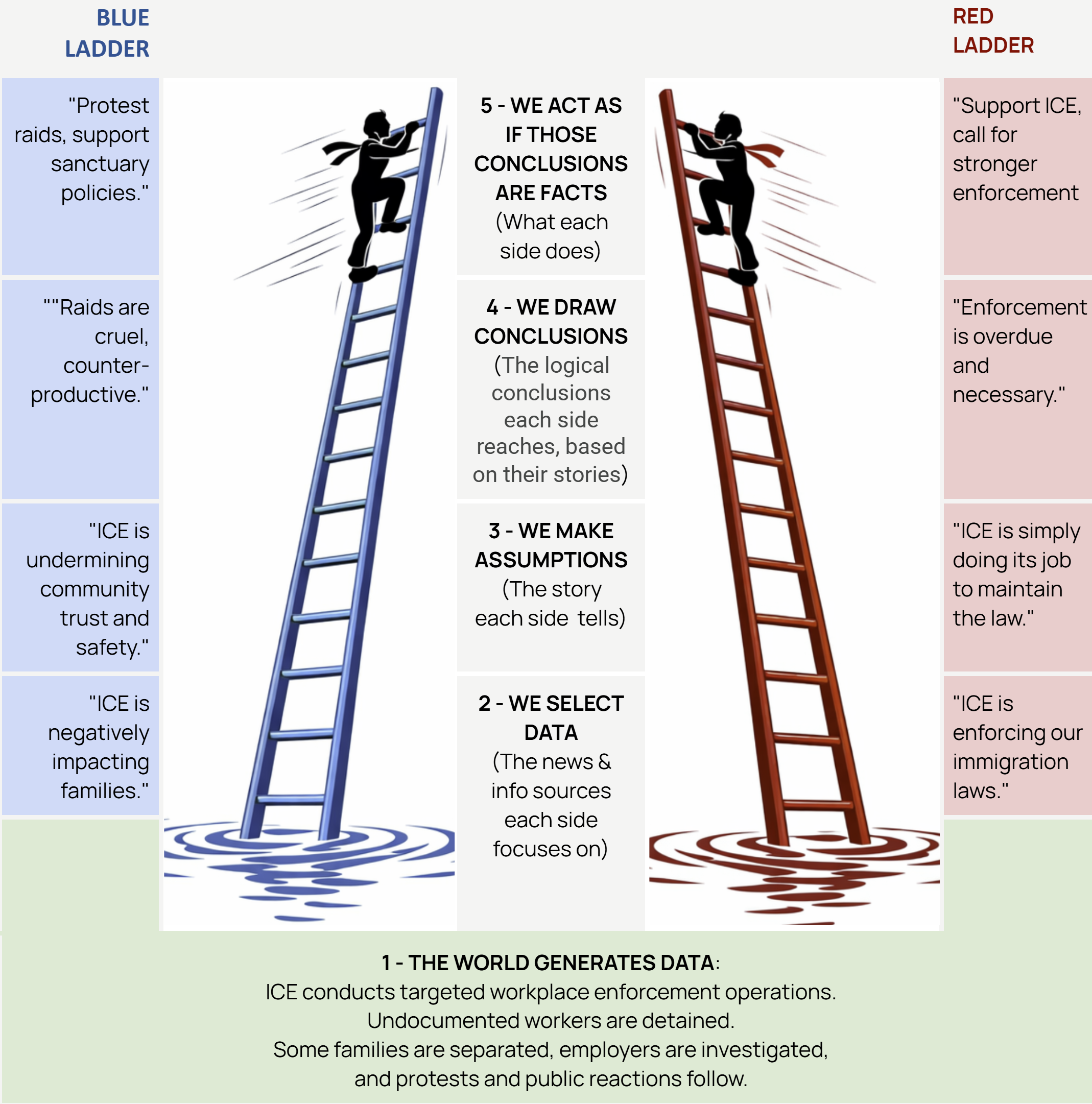

Understanding How We Become So Certain: The Ladder of Inference

To make this shift, I’ve found one tool particularly helpful: the Ladder of Inference 2. I introduce it to every leadership team I support.

The Ladder describes how quickly—and often unconsciously—we move from what we observe to what we believe is true. Understanding it can help us to catch ourselves when we are treating assumptions as if they are facts. When a group agrees to use it, it creates permission to respectfully challenge one another’s thinking.

Walking up the ladder happens in a flash:

The world generates data. (Millions of things are happening every second.)

We select data that stands out to us.

We make assumptions about what the data means.

We draw conclusions based on those assumptions.

We act as if those conclusions are facts. They become the “truth.”

Once we reach the top of the ladder, we forget that we climbed it. From the top, our view feels obvious. True. Moral. We can’t imagine how any sane person could see it differently. We then look for information that confirms our conclusions and avoid what might challenge them–classic confirmation bias.

If we want to shift polarization, we must learn to climb back down our ladders.

One Event.

Two Completely Different Ladders

Consider how different “ladders” are built around a single event, such as recent ICE enforcement actions. Reds and Blues have the same data. But they build very different ladders and arrive at very different conclusions.

Start at the bottom of this chart to understand how the mind builds the ladder and how thoughtful people reach very different conclusions.

A Political Example of the Ladder of Inference

Same event. Same basic facts. Entirely different ladders.

When we are at the top of our respective ladders, we confuse our conclusions with reality. We treat disagreement as a character flaw, rather than the result of different experiences, values, and fears.

We rarely pause to ask: What data might I be selecting—and what data might I be missing?

Instead, we assume we are right. And then we look for more data to confirm what we have concluded. And we can always find such data, especially if we don’t seek out information sources and conversations that challenge our thinking.

We live in news, social media, social, and political bubbles that reinforce how we already think. In the absence of information and relationship, we make up the worst stories about the “other.” We moralize. We assume they are bad and stupid people. This is how demonization takes root.

What If We Tried To Understand

Their Reasoning?

What if, instead of reinforcing each other’s certainty about the “other side,” we practiced something new? What if we shifted how we talk about people who hold seemingly opposite political and world views? What if we challenged our own assumptions? And used the Ladder of Inference as a tool to help us?

Shifting the toxic gossip mill where I worked in my twenties wasn’t easy. We didn’t do it perfectly or overnight. But because we agreed we wanted to make the change, we took on the challenge together. And we gave each other grace along the way.

I’ve seen the same thing with clients. When they redefine what it means to be a good colleague–moving from “be nice” and “pile on” to “challenge with compassion,” it’s a huge unlock. People speak more honestly. Energy increases. Agency returns.

What if we agreed to do the same thing inside our own political bubble?

A Simple Experiment To Try With “My Side”

The next time you get together with a group of friends on “your side,” invite them to try an experiment. “Instead of just complaining about the ‘other side,’ what if we tried something different today?”

Notice the negative assumptions we’re making about the “other side.” Let’s catch ourselves climbing the ladder of inference.

Where have we decided that the other side is malicious or stupid instead of simply having different concerns or fears?

Are we describing their positions as they would?

Generate “heroic” explanations. Challenge the group to imagine two hypotheses for why the other side’s position might be an intelligent, “heroic” choice from their perspective.

Challenge your own side’s thinking. Make it okay to ask, “What’s our actual data for that assumption?” or “What might we be missing?”

This takes immense courage.

Challenging friends and family who mostly agree with us often feels riskier than engaging with those who don't. But the alternative is to continue to reinforce a polarized system that we all say we want to change.

What Becomes Possible

When we change how we talk with our own people about the “other side,” something important shifts. We stop arguing with caricatures and start remembering that real people—neighbors, family members, fellow citizens—are doing their best to make sense of a complicated world.

We can interrupt polarization and demonization ourselves, one conversation at a time. And if we do it well, better ideas become possible. And if we do it well, better ideas become possible.

Stopping the toxic polarization gossip mill isn’t just about abandoning convictions or pretending differences don’t matter. It’s about taking responsibility for how polarization and demonization gets reinforced in everyday conversations–and refusing to keep feeding a cycle that’s making our country weaker.

We don’t have to wait for the media, political parties, or leaders to change. We can interrupt polarization and demonization ourselves, one conversation at a time.

We can start by remembering that we might love the people on the "other side" if we knew them. People like my family in Oklahoma, or my friends in San Francisco–people trying to live good lives, protect what matters to them, and act on what makes sense from where they stand.

Are we willing to slow down, climb back down our own ladders, and see what they see? And are we brave enough to ask our own side to do the same?